Fun with Falcons

In our last Forest Park Living Lab (FPLL) blog, Dr. Sharon Deem wrote about one of the great days that FPLL staff and volunteers spent at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. During this once-a-year event, we bring Forest Park wildlife artifacts, plush animals with the transmitters used on wildlife within the park, and our knowledge to share with the children and their families. I’m the lucky guy who gets to have a live bird of prey perched on my falconer’s glove, in a special room made just for visiting live animals.

Jeff Meshach and Cricket, the American Kestrel

I get to see, firsthand, the big smiles on the children’s, their parents’, and their relatives’ faces, as they gaze at the beautiful birds I bring. These special visits are so rewarding for me.

You may be surprised to know that just a few hundred yards east of this live animal room at the Children’s Hospital, a pair of Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) have been living and raising their many chicks, since early this century! In 2003, Washington University’s Medical School, which borders St. Louis Children’s Hospital, installed 3 falcon nest boxes to try to lure in a pair, and it worked.

Peregrine falcon, Aurora, at the entrance to one of her nest boxes by the Children’s Hospital

But why care, and what makes Peregrine Falcons so special? First and foremost, they are the fastest creatures on Planet Earth. They eat almost exclusively other birds, and with prey that can move and maneuver so quickly, it’s no surprise Peregrines must be fast and agile.

In a dive while trying to catch another bird, they have been clocked as fast as 261 miles per hour!

That’s considerably faster than the fastest Formula 1 car, which topped out at 231 MPH. To achieve and withstand such speeds, Peregrines have special adaptations that other birds don’t have.

The wing feathers that significantly contribute to bird flight are the primary and secondary feathers. The primaries are the longest wing feathers, furthest away from a bird’s body. During a bird’s powerful downstroke of the wing, the primaries help push them through the air. The secondaries are usually shorter than the primaries and closer to the body, located on a wing’s trailing edge. Secondaries aid in soaring and help the wing create lift.

A Peregrine’s wing has longer primaries and shorter secondaries compared to most of the world’s birds. Peregrines also have much stiffer feathers than other birds. This combination of long primaries, short secondaries, and extra stiff feathers allows Peregrines to achieve the great speed and agility they need to catch other birds in flight.

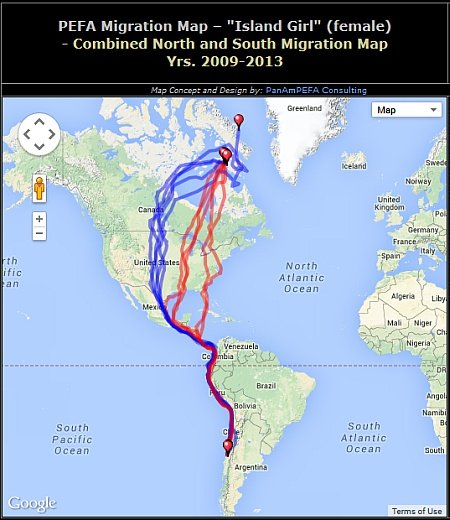

Want to know another awesome thing about Peregrines? They are the champions of long-distance migration in the birds of prey world. Peregrines are found on every continent except Antarctica. At the opposite end of the world from Antarctica, they migrate to and nest within the Arctic Circle. The Peregrines that nest within the Arctic Circle have been known to winter at the southern tip of South America; a distance of roughly 8,500 miles. And, you have to multiply 8,500 by 2 because they fly back to the Arctic Circle to nest in the summer.

Migration of a Peregrine falcon female. Photo from Outside My Window: A Blog of Birds & Nature, original data from the Southern Cross Peregrine Project and Falcon Research Group

Also, Peregrines can migrate over the open ocean, hundreds of miles away from the closest land. No other raptors in the world can do this. Peregrines can catch and eat their prey as they migrate. To me, we are privileged to have about 8 nesting pairs of Peregrines in our area, let alone to have a pair nesting so close to Forest Park.

Not only do we have bird world royalty living so close to (and probably hunting within) Forest Park, we actually know where the female of the current pair was hatched and raised. One of my favorite things to do in the world is to place bands on wild Peregrine Falcon chicks.

I’m the lucky guy that gets to visit the Peregrine nests in the greater St. Louis area, usually during the month of May, collect the chicks and place bands on their legs. Each leg gets a band. The band that’s placed on the left leg has 2 colored fields, and within the colored fields are white numbers and/or letters. These letters and numbers are large enough to be seen from a distance with a good pair of binoculars. Because of this special band, we, raptor researchers and Citizen Scientists (like you!) can gather information without needing to have the falcon in our hands. Because of this special band, we know the female in our pair was banded as a 22-day-old chick on 30 May 2008 from a falcon nest box on the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. She was given the name Aurora by the Peregrine researcher who banded her.

Aurora flashing by her nest on chick banding day. Photo taken by Dawn Griffard.

We know of at least 2 other females and males that have made up the Forest Park pair, but Aurora has been the female since 2015. Seventeen years old is quite old for a Peregrine falcon. Old age presents challenges to her reproductive prowess. During the 2025 nesting season, she laid 4 eggs (a typical clutch size for Peregrines), but only one hatched and was banded. Since becoming the breeding female of this pair, Aurora has successfully raised 35 chicks. She may have slowed down, but she sure has contributed to the survival of her species!

By: Jeff Meshach, Deputy Director, World Bird Sanctuary, and FPLL team members